Róska (1940-1996) belonged to the generation of radical European artists who wished to expunge the boundaries between life and art, who fought against the artistic snobbery of the bourgeoisie, the political complacency of the masses, and the propaganda machinery of professional politicians. Róska was a painter, a photographer, a film director, and – above all – an insurrectionist; the theme of her life is “continual rebellion in living poetry and politics,” as she herself said in a 1978 article about surrealism.

She lived in Rome for the majority of her life, but to Icelanders her life was cloaked in the robes of adventure, even legend, because of her personal charms, artistic talent, political radicalism, and aura of things Southern. Nonetheless her life evolved into a tragedy due to the burden of chronic illness and her eventual downward spiral into the world of drugs.

Her real name was Ragnhildur Oskarsdottir and she was born in Reykjavik. She became epileptic after an accident at the age of 14; in the years that followed she travelled widely in Europe with her father in search of a cure.

Her father, a chemical engineer, came from a very poor family and for years served on the Board of the Cultural Society of Iceland and the Soviet Union. After quitting secondary school, Róska worked in the first privately owned gallery in Iceland and then began her studies at the Icelandic College of Art and Crafts. She studied in Prague

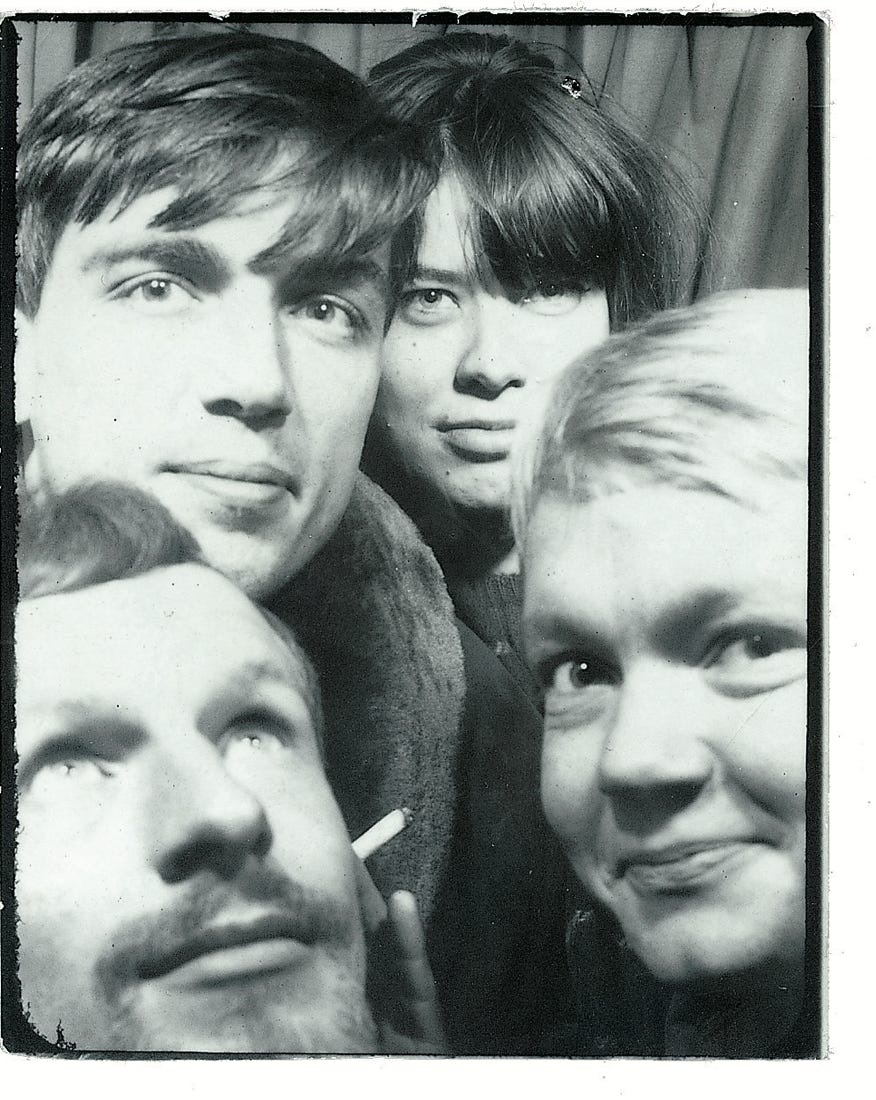

for one year and spent another in Paris, after which she enrolled in L’Accademia di Belle Arti in Rome, where she remained for two years. On the occasion of her first private exhibition in Reykjavik in 1967 in a gallery called Casa Nova, she said in newspaper interviews that she didn’t think much of the Academy in Rome. She described commune life in Paris and Rome and allowed as how she didn’t think it would be easy to live the life of an artist in Reykjavik because it was so bourgeois. “Her appearance brought the South with it,” writes author Gudbergur Bergsson, „and immediately life in Reykjavik became, for some, stale as canned fruit in a fruit pie. Her hair, her smile, everything in Róska’s bearing was somehow natural, carefree, beautiful – her talent undeniable“.

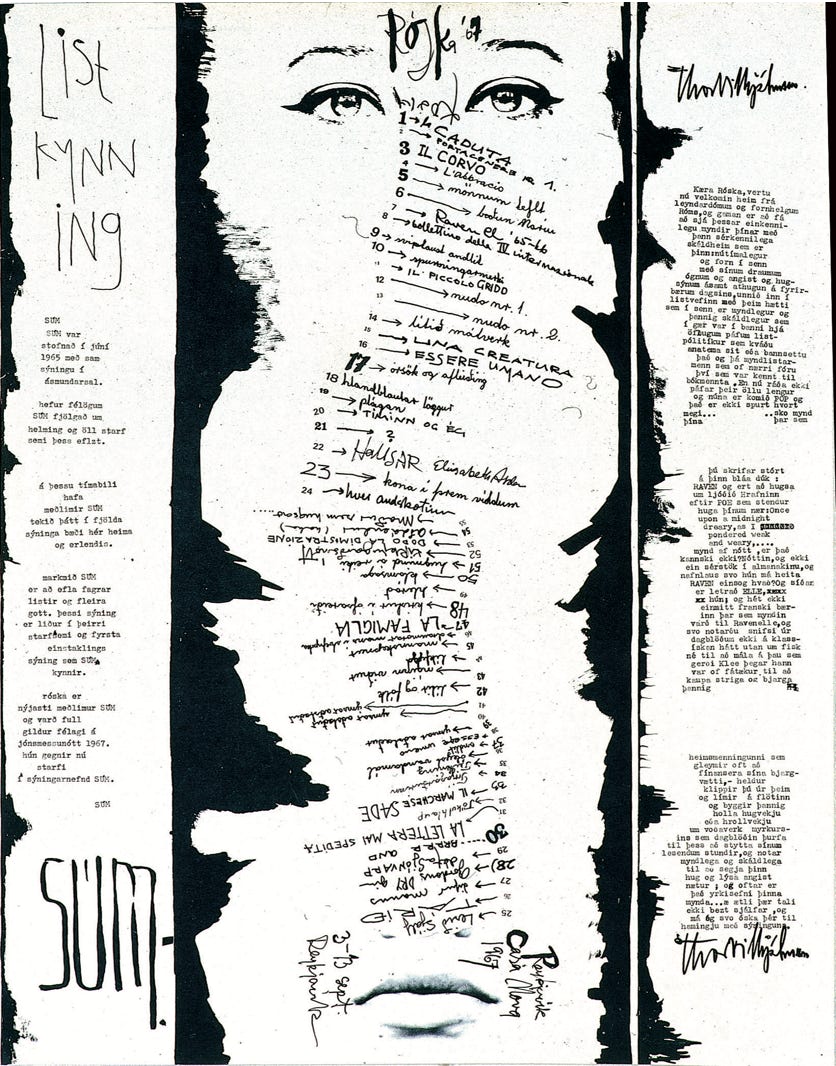

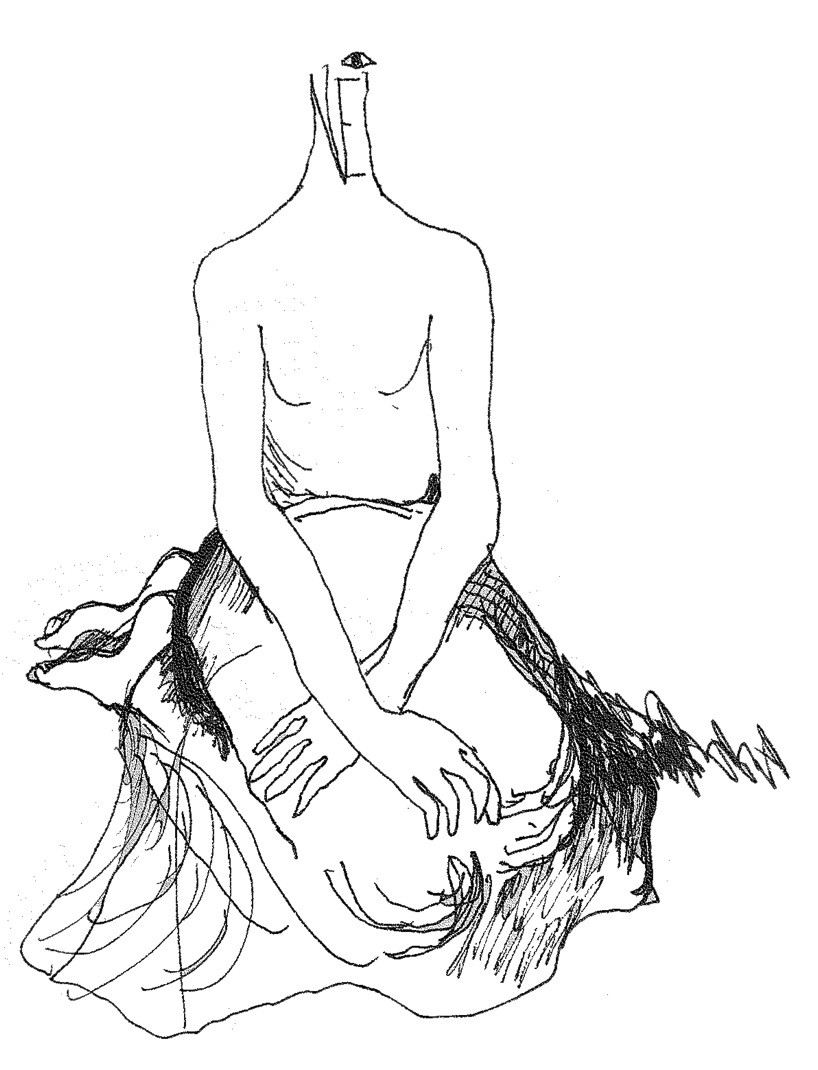

The exhibition in Casa Nova attracted a great deal of attention. It consisted of 55 paintings and drawings mostly in figurative expressionistic style, but with a few which called to mind the irony of pop art. Art historian Halldor Bjorn Runolfsson was 17 years old when he saw the exhibit, which he claimed was a turning point for him. At that point he had never seen art which treated contemporary life. He refers to Róska as a superb draftsman and speaks of an anguish and an ebullience in her drawings – qualities he finds rare in Icelandic art. The exhibit was advertised as “an artistic introduction by SUM,” a group of young avant-garde artists who would later have great impact on Icelandic art. Róska was invited to join the group and at that time participated in an outdoor exhibition, where she set up a washing machine transformed into a rocket launching pad. This was likely the first feminist work of art in Iceland, and it elicited such enthusiasm, according to her friend, the poet Baldur Oskarsson, that it was stolen a few days after the opening of the exhibition.

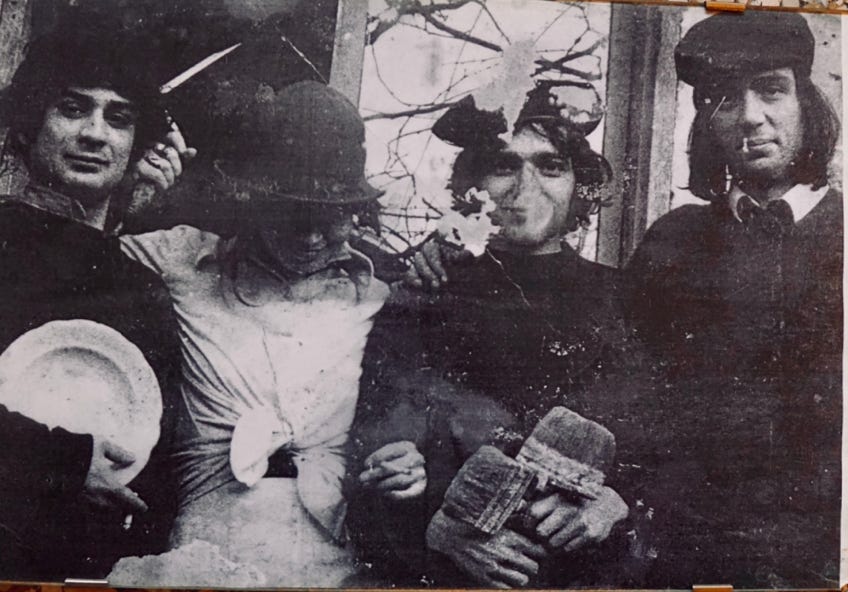

While in Rome, Róska met the talented young poet Manrico Pavolettoni, who would later become her husband. Their large apartment in Via Giulia quickly became a domicile for young artists in the city. Their guests came from all directions, from the United States, France, Holland, and Iceland, as well as Italy; for, unusual as it may seem, Reykjavik and Rome were alike in that neither city offered a public forum for avant-garde art. It was precisely for this reason that the artistic commune in Via Giulia was important. Icelandic artists who visited Via Giulia during those years agree that Róska was a leader in the group; she painted furiously during the first years and quickly became well known in the city. From 1967 on, her works became more political, and she discovered a medium which young radical artists had great hopes for: cinema. The first film she acted in, shot in Rome in 1967, was

cameraman was a young American named Tony Luraschi, the son of the Chief Executive of Paramount Pictures. The male lead was played by Icelandic artist Hreinn Fridfinnsson, who then lived in Via Giulia and was one of the founders of SUM. The film was shown two years later at a SUM exhibition, but all copies of it have since been lost.

In 1969 Róska was connected in some unknown way with two movies which Jean Luc Godard filmed in Italy: La Lutte ouvrière en Italie and Vento del Est. Godard had by this time turned to the making of political documentaries and had founded a group, consisting of students and young filmmakers, which identified itself with the Russian cinematographer Dziga Vertov. Disagreement quickly surfaced between the Maoists and the anarchists in the group. Godard considered himself a Maoist, but Róska and her comrades saw themselves as anarchists and finally produced their own full-length film, entitled L ́Impossibilità di Recitare Elettra Oggi. The film tells the story of young people who intend to stage a production of Sophocles’ Electra but come to the conclusion that it is impossible, that the only true art is in the dialogue of people who involve themselves in the battle of the common worker and rebel against authority. The inspiration for the film was a series of events that took place in 1968 in the Northern Italian village of Fabbrico, where workers and students took control of a meeting-house and a cinema. Róska herself participated in the happenings in Fabbrico, which profoundly influenced her, as her diaries show clearly.

But it was not only in Italy that Róska was active in 1969. She came to Iceland in the fall with two companions and announced in newspaper interviews that she intended to film a documentary of protest in Iceland. In addition, she and her colleagues had with them several documentary films of student riots and protest marches in Paris and Rome and invited the Icelandic public to see them. That same autumn Róska participated in a huge international SUM- exhibition in Reykjavik (SUM III), where – among others – works by Joseph Beuys, Robert Filiou and Daniel Spoerri were shown. In preparing the exhibit, the members of SUM benefited greatly from the international connections of Dieter Roth, who was then living in Iceland. Róska’s contribution to SUM III was a gigantic molotov cocktail, a revolutionary’s suitcase, propaganda posters, and a barricade, presented under the title „The Work of Revolutionary Student and Labor Unions in Italy“. She was asked to give a lecture on contemporary art at Reykjavik Junior College and showed only slides of political graffiti in Rome, informing the lecture hall jammed with students and teachers that this was contemporary art.

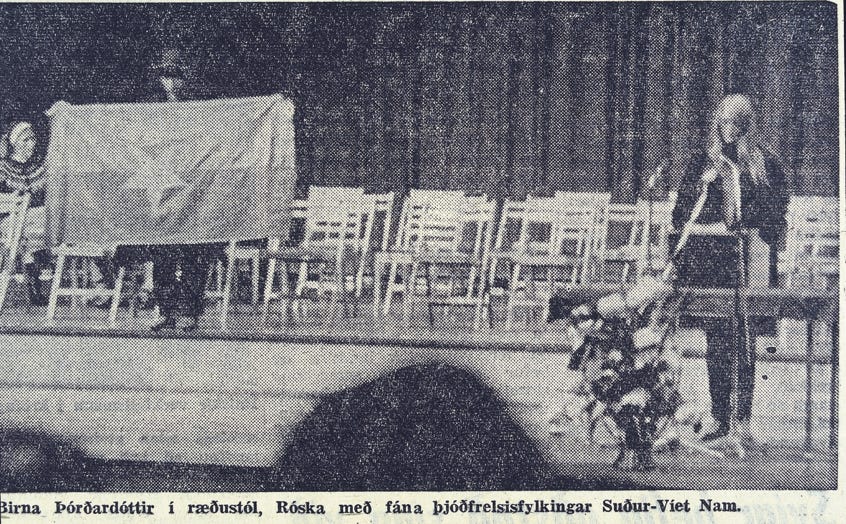

She became embroiled in a public editorial debate over a large photograph of riot police on which was written “oppression, violence, murder”. The picture was rejected by an exhibit held by the Society of Icelandic Artists. In November of that same year, she was responsible for two political spectacles in true situationist spirit: she stirred up a festival in honor of Icelandic Nobel laureate Halldor Laxness, then went on stage waving a North Vietnamese flag while her friend Birna Thordardottir gave a speech protesting American military involvement in Vietnam and Icelandic support thereof, as well as lamenting that fact that Halldor Laxness should have become the friend of this same bourgeoisie which formerly hated him. The following day, accompanied by a handful of other Icelandic radicals, Róska stormed into the US Naval Air Base in Keflavik, gained entry into the television studio, and stopped the broadcast for a good half hour by spraying red paint on the lenses of the cameras and then painting the words VIVA CUBA! and BRAIN WASHING CENTER on the walls of the studio. But it must be mentioned that the television broadcasts of the US Naval Base were shown widely in Iceland and that Icelandic leftists, not to mention a few right-wingers, considered them a threat to the cultural independence of the country.

In 1971 Róska participated in a group exhibition which SUM was invited to hold in the Fodor Museum in Amsterdam. During the 70s she took part in several collective exhibits in Iceland, Italy, and Spain, but she spent most of her energy on political battles, designing propaganda posters, newspapers, and magazines published by radicals in Iceland and Italy. In Italy she became a vigorous participant in the movement which identified itself with the periodical Lotta Continua and thus became connected with the Red Brigade (brigade rosso), where her role included making counterfeit passports for members of the Brigade. In 1973 she enrolled in the Centro Experimentale Dell’Arte Cinematografica in Rome. During the years from 1974 – 76, she and Manrico made eight

Il Uomo delle Folla, based on the Edgar Allan Poe story A Man in the Crowd. The director was Oddo Bracci, and the 3⁄43⁄4 documentary films on Iceland for Italian television. The Icelandic Broadcasting Company refused to show them. Róska and Manrico travelled often to Paris around this time and met, among others, the French actress Bulle Olgier; in 1975 Róska worked on the Jacque Rivette film Duelle. In 1977 the 35-minute film The Ballad of Olafur Liljuros, based on an Icelandic folk tale, was shown in Iceland; Róska wrote the script for it as well as writing and directing the full-length film Soley, premiered in 1982, which also is derived from motifs in Icelandic folk tales. Both films were technically primitive and received, for the most part, indifferent reviews.

The direction Róska took with these two films seems a little peculiar, perhaps, if one considers how fervently she had sought out the vortex of the international artistic avant-garde. But it must be borne in mind that the pictures The Ballad of Olafur Liljuros and Soley both have a surrealistic air and, despite the ethnic motif taken from Icelandic farming society, may be seen as allegories for the life struggle of oppressed socioeconomic groups. The enemy, though, is no longer capitalism as a world power but rather the fetters of the human mind, which prevent people from daring to realize their dreams. Róska has, then, begun to look to surrealism instead of practicing direct political propaganda. Actually her friend Hreinn Fridfinnsson maintains that the poetical vision was the strongest element in Róska’s life and work, that her straight-shooting politics had been a function of externals, something that had floated in the ambience of the times.

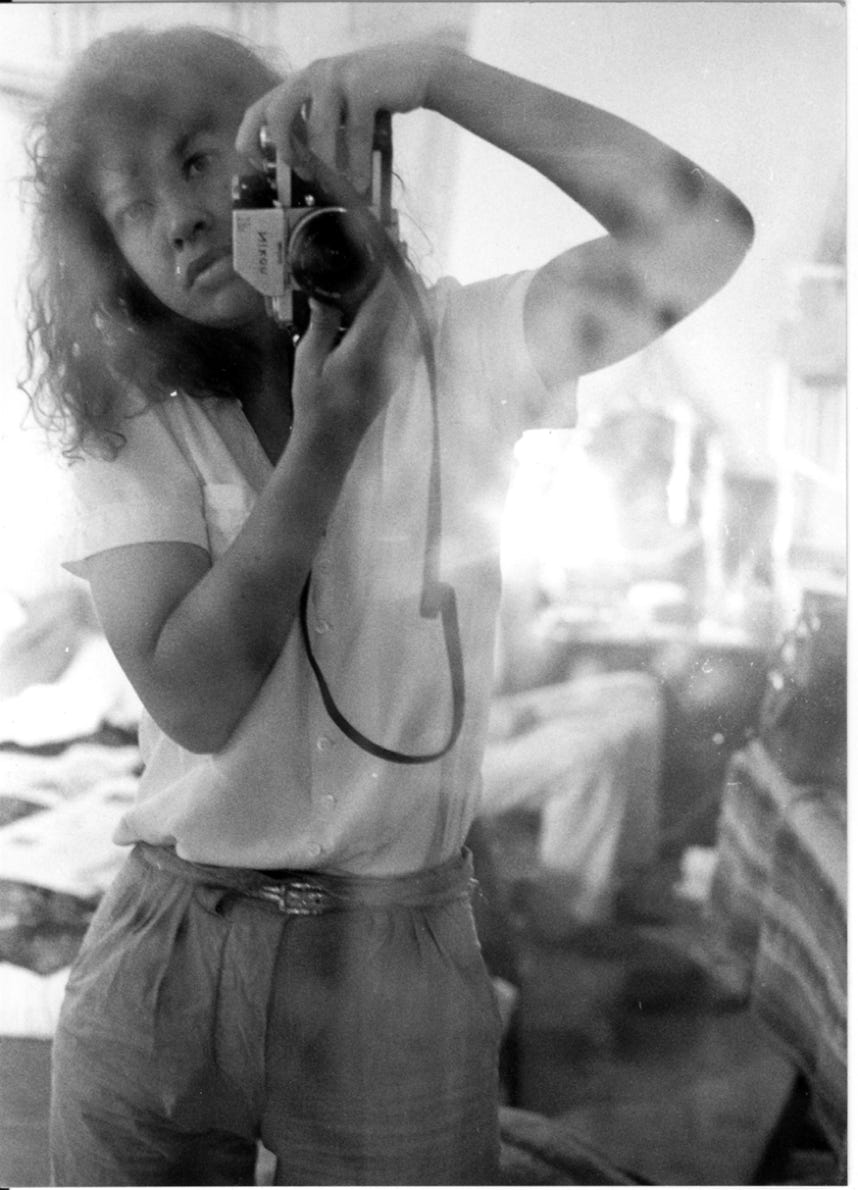

During the1980s it seemed as though Róska had withdrawn permanently. There were many reasons for the change: her health had worsened greatly because of her epilepsy; the film Soley lost a large amount of money, placing a heavy financial burden on many of her Icelandic friends; and Róska and Manrico’s drug used increased markedly. In 1990 she held an exhibit at Nylistasafnid (The Living Art Museum), where she showed oil paintings, sketches, and photographs; she had been a passionate photographer from early in the 1970s. Most of the works in this exhibition were from around 1980; but there were also computer-generated works, giving rise to the opinion that Róska was the first Icelandic artist to produce art with the help of computer technology. She held another exhibition in Reykjavik in 1993 – having then relocated from Rome to Iceland – entitled “Woman 2000”.

In 1996 the Living Art Museum invited Róska to hold a large overview exhibit of her works. This exhibit was

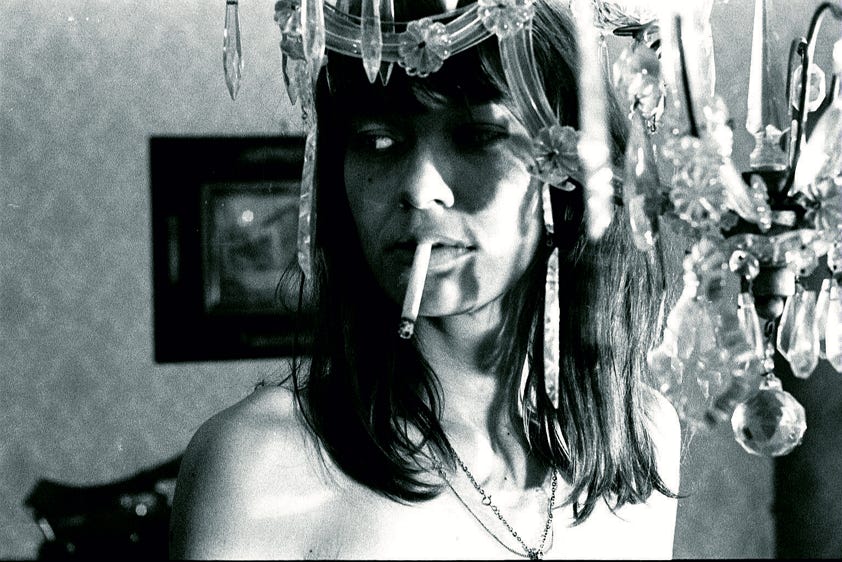

in preparation in March when she held a publicly advertised “performance” in the Living Art Museum. The “performance” began with Róska lying on a dirty mattress on the floor.

Cinematic light projectors illuminate the scene from outside the windows. She wakes up, all surrounded by empty beer bottles; she lights a cigarette, kicks the bottles. She turns on the television with the remote control, talks to herself, curses. In a bag on the floor are tubes of paint; she picks them up one after the other and throws them at a dartboard, aiming badly. Then she turns on an overhead projector which casts photographic images from her life onto the taut canvas on the wall, and she paints over every photo. She thus changes her life into a painting, and the “performance” ends with her donning a pair of professorial spectacles and reading the article on surrealism which she had written many years before. In a sense it can be said that she was thus formally dedicating her life to surrealism; as she writes in the article, I’m tired of wading in dreary gray concrete. When I woke up this morning I tried to console myself with the words of the Feminist-Activists, „Woman is Beautiful,” but I was immediately put off course by Baudelaire’s observation, “Beauty is always peculiar,” so I decided to take a shower. Two weeks later Róska was dead.